Data (based on the original strain of COVID-19) suggest that children (especially children aged less than 12 years of age) are less likely to be infected compared to older children and adults. There is no evidence to suggest that the current delta strain is more likely to infect children compared to previous strains. And even if children are infected, they generally experience mild illness. So far, most severe cases have been in elderly people with medical conditions such as heart problems or lung disease. There have been very few children across the UK admitted to hospital with severe COVID infection. This includes children with other health conditions, including those undergoing treatment for cancer or those with weakened immune systems or respiratory conditions - even they have generally experienced mild infection when infected with COVID. Reassuringly, during December 2020, when children were still at school and the new COVID strain was circulating, very few children were admitted to hospital with severe COVID infection.

Although there are very little data to clearly identify any specific groups of children at risk of severe infection, it appears that children with severe neurological (brain) conditions that affects their breathing, as well as children with Down's syndrome and those with weakened immune systems are perhaps at higher risk of getting unwell if they contract COVID. For this reason, the government has announced that vaccination should be considered for children aged 12-15 years with these conditions (as of 4/8/21, COVID-19 vaccination is recommended in all children aged 16 years and over). At present, there are no COVID-19 vaccines licenced for children below 12 years of age. For more information about UK COVID-19 vaccine recommendations in children, click here.

For specific information for children and young people with cancer undergoing cancer treatment, click here.

If you are worried about your child's breathing and are not sure if they need to be seen by a healthcare professional, click here to help you decide. Our local and regional paediatric services are well set up and have detailed plans in place to treat and support all children who have severe COVID-19 disease. There is a national plan in place for children that require intensive care support (PICU).

If any member of your family is infected with COVID-19, then your whole family needs to self-isolate for 10 days. The main reason for this is to reduce the risk of the virus being transmitted to others outside of your household. There is a high risk of other household members being infected and if this occurs, you need to restart the 10 day period of self-isolation for those not already infected.

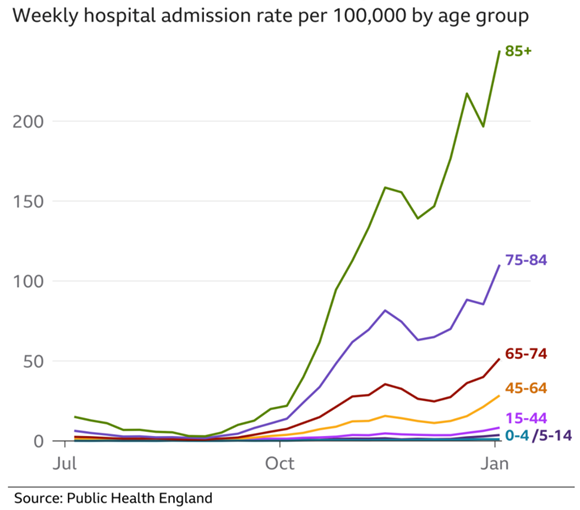

Avoiding infection is obviously most important for people at the highest risk of becoming unwell from COVID-19. This includes the elderly and adults with long-term health problems such as breathing problems, heart problems, chronic kidney or liver disease, those with central nervous system conditions and those with weakened immune systems. This approach is called social distancing and is the most effective way of minimising the impact of this pandemic. For parents, this means trying to minimise the contact that your child/children have with people from vulnerable groups. This is because children may have the infection with almost no symptoms and potentially may infect other people. This is the reason that the government have decided to prioritise the vaccine for those most vulnerable to severe disease. Even following the vaccine, it takes 21 days to develop good levels of protection. Minimising contact between children and the most vulnerable individuals awaiting vaccination is important whilst this new stain is circulating.

It is extremely important to realise that not every child with a fever has COVID-19. All the other conditions that can make children unwell are still ongoing during the COVID-19 pandemic. If you are not sure if your child is unwell and whether they need to be seen by someone, take a look at the red / amber / green criteria below to help you decide.